🚀 CloudSEK becomes first Indian origin cybersecurity company to receive investment from US state fund

Read more

Key Takeaways:

A reverse shell attack is a technique where an attacker gains control of a system by making it connect back to the attacker’s machine. Instead of the attacker reaching into the network, the compromised system initiates the connection, allowing remote command execution in a less obvious way.

This approach is commonly used because outbound connections are often trusted and monitored less closely than incoming ones. As a result, reverse shell activity can blend into normal network traffic, making it harder for traditional security defenses to detect and block.

A reverse shell works by getting a compromised system to reach out to an attacker instead of the attacker trying to break in. That outbound connection becomes a live control channel where commands can be sent and executed remotely.

The process starts when the infected system opens a network connection back to the attacker using TCP/IP. Since this traffic is leaving the network, it usually slips past firewalls and NAT controls without much resistance.

On the other end, the attacker has a listener waiting for that connection. Once it’s accepted, the attacker gains a direct line to interact with the target system.

The system then ties its local shell, such as Bash or PowerShell, to the open network socket. This setup allows everything typed by the attacker to be processed as if it were entered locally.

Commands are sent across the connection and run instantly on the compromised host. The results are sent back the same way, keeping the session active and interactive.

Attackers prefer reverse shells because inbound connections to internal systems are commonly blocked. A bind shell requires the attacker to connect directly to the victim, which is often prevented by firewalls.

Reverse shells invert this model by using outbound traffic, which most networks allow by default. This makes reverse shells more reliable across corporate, cloud, and containerized environments.

Most security architectures focus on filtering inbound traffic while trusting outbound connections. Reverse shells exploit this trust by using egress traffic that appears legitimate.

Attackers may also use common ports and protocols associated with normal services. This allows reverse shell traffic to blend in with regular network activity, reducing the likelihood of detection.

Reverse shell attacks usually depend on tools that are already trusted, installed, or commonly used in everyday systems. This makes the activity easier to hide, since the tools themselves aren’t malicious until they’re used in the wrong context.

Netcat is widely used because it can create simple network connections with very little setup. Attackers often abuse it to pass shell input and output directly over a TCP/IP connection.

Built-in shells like Bash on Linux and PowerShell on Windows play a central role once access is gained. Since these shells are meant for legitimate administration, their misuse can blend in with normal system behavior.

Frameworks such as Metasploit are commonly used to deliver and manage reverse shells at scale. Its Meterpreter sessions provide stable access, session handling, and extended post-exploitation control.

Languages like Python and Perl are often leveraged to create lightweight reverse shell payloads. Their availability on many systems allows attackers to operate without dropping obvious external binaries.

In many cases, attackers rely entirely on existing utilities already present on the system. This “living off the land” approach reduces noise and makes reverse shell activity harder to spot through traditional security controls.

Detecting a reverse shell attack depends less on spotting specific tools and more on recognizing unusual behavior. Since reverse shells use legitimate processes and outbound traffic, visibility across both the network and endpoints is critical.

Unexpected outbound connections are one of the strongest indicators of a reverse shell. Connections to unfamiliar IP addresses, odd ports, or rare destinations should always raise suspicion.

Reverse shells often create long-lived or repetitive connections that don’t match normal application behavior. Sudden spikes in encrypted or raw TCP traffic can also signal hidden command-and-control activity.

On the endpoint, a common sign is a shell process launched by an unusual parent application. For example, a web server or background service spawning Bash or PowerShell is rarely normal.

Frequent command execution without user interaction is another warning sign. When systems run commands outside of scheduled tasks or administrative workflows, it often points to active attacker control.

Tools like EDR, IDS, and SIEM platforms help correlate network and endpoint signals. By combining logs, alerts, and behavioral data, security teams can detect reverse shells before they escalate into larger breaches.

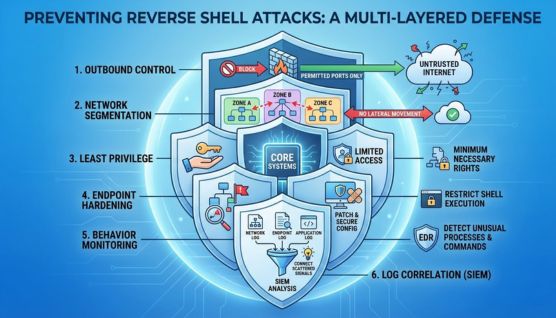

Preventing reverse shell attacks is mostly about reducing exposure and tightening control over outbound activity. Since these attacks rely on trusted tools and normal-looking traffic, prevention works best when multiple security layers work together.

Restricting outbound network traffic is one of the most effective defenses. Egress filtering ensures systems can only communicate with approved destinations and required ports.

Segmenting networks limits how far an attacker can move after gaining access. Even if a reverse shell is established, segmentation reduces lateral movement and overall impact.

Users and services should only have the permissions they actually need. Limiting privileges reduces what an attacker can do even if shell access is obtained.

Keeping systems patched and securely configured closes common entry points used to deploy reverse shells. Application control and execution restrictions further reduce abuse of system shells.

Endpoint Detection and Response tools help spot suspicious shell activity early. Watching for unusual parent-child processes and unexpected command execution is key.

Centralized logging through SIEM platforms helps connect small warning signs across systems. Correlating network, endpoint, and application logs improves early detection and response.

Reverse shell attacks are most often seen in environments where systems are exposed to the internet and outbound traffic is loosely monitored. Modern infrastructure has expanded the attack surface, giving attackers more opportunities to quietly establish remote access.

Cloud workloads are frequent targets, especially when virtual machines or services are misconfigured. Exposed management ports, weak credentials, and overly permissive security groups make it easier to deploy reverse shells after initial access.

Containers and Kubernetes clusters are attractive because a single weakness can expose multiple workloads. Attackers often use reverse shells to move from a compromised container to the underlying host or other services in the cluster.

Public-facing web applications remain one of the most common entry points. After exploiting vulnerabilities like file upload flaws or command injection, attackers use reverse shells to gain persistent backend access.

Build servers and automation tools are increasingly targeted due to their elevated permissions. A reverse shell in a CI/CD environment can give attackers access to source code, secrets, and deployment systems.

Employee workstations are also common targets through phishing or malicious downloads. Once compromised, reverse shells allow attackers to maintain control and pivot deeper into internal networks.

Reverse shell risk goes far beyond simple system access. Once a reverse shell is active, it often becomes the gateway to broader compromise across systems, data, and operations.

A reverse shell gives attackers interactive access to the operating system. This allows them to modify configurations, install additional tools, or disable security controls.

Attackers can access sensitive files, databases, and credentials directly from the compromised host. This often leads to data theft, intellectual property loss, or leakage of customer information.

With shell access, attackers can explore the internal network and pivot to other systems. One compromised machine can quickly turn into a wider breach.

Reverse shells are frequently used as a starting point to gain higher-level permissions. If successful, attackers can take control of critical services or administrative accounts.

Attackers often use reverse shells to establish long-term access. They may create hidden backdoors or scheduled tasks that survive reboots and updates.

Systems under attacker control can be altered, corrupted, or taken offline. In severe cases, this results in service outages, downtime, or ransomware deployment.

Data exposure and unauthorized access can trigger regulatory violations. Organizations may face audits, fines, legal action, and visible reputational damage.

To further reduce reverse shell risk, security teams should look beyond obvious network and process signals and focus on subtler infrastructure and behavior clues. These indicators often surface earlier in mature environments where basic monitoring is already in place.

Unusual DNS queries can reveal reverse shell infrastructure before connections are fully established. Repeated lookups to newly registered or low-reputation domains are especially suspicious.

Web proxies often capture outbound behavior that firewalls miss. Reverse shells tunneled over HTTP or HTTPS may show abnormal request patterns or unusual destination usage.

Even when traffic is encrypted, TLS metadata still provides value. Rare certificates, uncommon cipher usage, or mismatched server names can indicate covert command-and-control channels.

Monitoring changes in approved outbound destinations is critical. Systems suddenly communicating outside defined allowlists may signal unauthorized remote control attempts.

In cloud environments, control-plane logs often expose attacker activity. Unexpected API calls, role changes, or metadata access can indicate shell-based exploration.

At the container level, runtime events provide key context. Shell access inside containers that normally run single-purpose services is a strong anomaly.

Reverse shell activity often occurs outside normal operational hours. Command execution or outbound communication during off-hours should be reviewed carefully.

Reverse shell attacks remain effective because they take advantage of the implicit trust built into modern networks and systems. By relying on legitimate tools, outbound connections, and normal system behavior, attackers can stay hidden while maintaining deep control.

Defending against this risk requires more than blocking traffic or deploying security tools. Organizations that understand how reverse shells operate and actively monitor behavioral signals across cloud, endpoint, and network layers are better equipped to detect intrusions early and reduce real-world impact.