🚀 CloudSEK becomes first Indian origin cybersecurity company to receive investment from US state fund

Read more

Command & Control (C2) servers are malicious servers used by attackers to remotely manage and control systems infected with malware. They act as the communication point through which compromised devices receive instructions or send stolen data.

The need for centralized control emerged as malware campaigns grew beyond isolated infections and required coordination across multiple machines. Defensive advances later pushed attackers to modify how C2 communication is structured and delivered.

C2 servers remain essential to modern cyberattacks because they support continued attacker presence after an initial breach. Understanding their purpose helps explain how intrusions persist even when no visible activity occurs.

A Command & Control (C2), also known as C&C, describes the control layer attackers rely on after malware execution rather than the malware itself. Its defining role is to enable remote instruction and feedback between attackers and compromised systems.

Unlike legitimate servers, a C2 server is designed to operate covertly and maintain long-term access within a victim environment. Communication is structured to resemble normal network behavior so it can persist without drawing attention.

From an attacker’s perspective, the C2 server functions as the coordination point for ongoing malicious activity. From a defensive standpoint, it represents the communication channel that must be disrupted to stop an active intrusion.

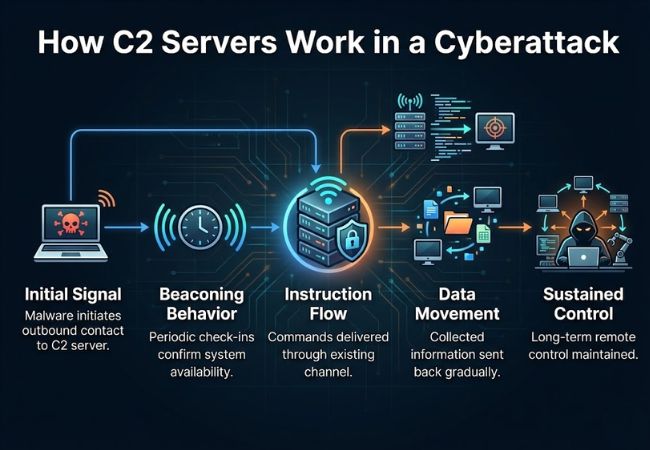

A Command & Control (C2) server works by acting as the communication bridge between an attacker and malware running on a compromised system.

Once malware is active on a compromised system, communication is initiated toward the C2 server rather than the attacker connecting inward. This outbound interaction reduces exposure and allows control to occur quietly through normal network paths.

C2 communication appears as repeated but limited network signals instead of continuous traffic. These signals allow the attacker to know the system is still reachable while avoiding patterns that stand out.

Commands move from the C2 server to the malware through the same communication channel already in use. This design allows attacker actions to change without reinstalling malware or re-entering the system.

Information collected by malware, such as system details or stolen data, travels back to the C2 server in controlled portions. Sending data gradually helps the activity remain hidden within regular traffic.

As long as communication with the C2 server remains intact, attacker control persists over the compromised system. This sustained access enables long-term intrusion without visible signs of ongoing attack activity.

Malware becomes significantly more flexible once ongoing communication with a C2 server is in place. Actions no longer need to be preprogrammed at the time of infection and can instead be directed remotely.

Instructions originate outside the compromised system and are delivered through the C2 channel. This separation allows attackers to decide how and when malware should act without modifying the original infection.

New capabilities can be introduced long after the initial compromise. Additional components arrive through the same communication path, allowing malware behavior to evolve as conditions change.

Information gathered from compromised systems does not leave the network arbitrarily. Movement occurs through the C2 channel, which provides a controlled and predictable path back to the attacker.

Individual infections gain relevance when viewed together rather than in isolation. A single C2 server can direct activity across many compromised systems, enabling coordinated actions at scale.

Continued access depends less on exploitation and more on communication. As long as the C2 channel remains active, control over the compromised environment can be maintained.

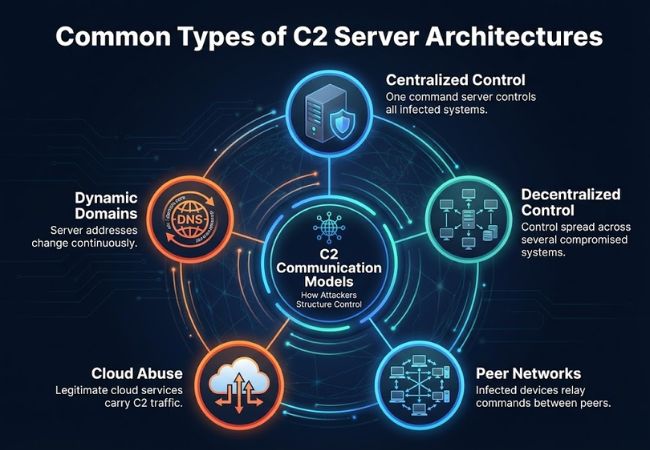

Differences in C2 servers are mostly shaped by how communication is organized and how much resilience attackers need during an operation. These variations affect how easily control can be disrupted and how long an intrusion can persist.

One server acts as the single point through which all compromised systems receive instructions. This model is simple to manage but becomes fragile if the server is identified and taken offline.

Control responsibilities are distributed across multiple compromised systems instead of a single server. Removing one node has limited impact, which makes disruption more difficult and slower.

Infected systems communicate directly with each other to relay commands. Control can move dynamically within the network, reducing reliance on fixed locations.

Legitimate cloud services are used as intermediaries for command communication. Normal service traffic helps malicious activity blend in and complicates filtering efforts.

Server locations change frequently through automated domain generation. Blocking one address provides little benefit because new communication paths appear quickly.

C2 servers appear across multiple attack scenarios because they support control, coordination, and persistence after initial access. Their usage changes depending on attacker objectives and the nature of the compromised environment.

Advanced Persistent Threats rely on C2 servers to maintain long-term access to targeted systems. Ongoing communication allows attackers to observe activity, adjust behavior, and remain present without triggering immediate disruption.

Ransomware Attacks use C2 servers to coordinate execution across infected systems. Communication may support encryption control, timing decisions, or interaction with affected environments after deployment.

Banking Trojans depend on C2 servers to manage credential theft and transaction monitoring. Centralized control allows stolen financial data to be collected and processed without direct access to each infected device.

Some attacks focus on harvesting authentication data rather than immediate disruption. C2 servers provide a channel through which credentials can be gathered gradually and reviewed remotely.

Initial compromise often serves as an entry point rather than a final objective. Commands issued through a C2 server can guide movement into additional systems within the same environment.

Tasks such as running commands or activating dormant malware features are triggered through the C2 channel. This allows actions to occur without re-infecting systems or re-establishing access.

Certain operations emphasize persistence over speed. Continued communication with a C2 server allows attackers to remain embedded while objectives evolve over time.

The danger of C2 servers lies in what happens after initial access rather than how that access is achieved. Continued communication allows a single compromise to develop into a sustained security issue that is difficult to isolate and fully resolve.

C2 communication is structured to resemble normal network traffic. This similarity allows malicious activity to remain hidden for long periods.

Attacker control does not end once the original vulnerability is addressed. An active C2 channel can preserve access even after systems appear to be patched or cleaned.

Actions directed through a C2 server often occur incrementally rather than all at once. This slow progression reduces visibility while increasing overall damage.

Sensitive information can be collected and transferred in small portions over time. Such controlled movement lowers the chance of triggering immediate alerts.

Removing malware alone does not always break attacker control. As long as C2 communication persists, remediation efforts can be incomplete or reversed.

C2-driven activity can affect availability, integrity, and reliability of systems over extended periods. The resulting disruption may be subtle at first but grow more severe over time.

Detection of C2 servers relies on recognizing communication behavior that does not align with normal system activity. Visibility develops through patterns that repeat, correlate, or persist rather than a single isolated signal.

Outbound connections to unfamiliar external destinations often attract attention during analysis. Repeated communication with the same endpoint can indicate centralized control.

Automated communication commonly follows consistent or algorithmic intervals. Regular check-ins without clear user or application context often signal hidden control channels.

Protocols such as HTTP, HTTPS, or DNS may carry command traffic in unexpected formats. Encoded payloads or unusual request structures can suggest misuse.

Low-reputation or recently registered domains frequently appear in C2 activity. Rapid shifts between destinations may also reflect attempts to evade blocking.

Encryption conceals content but leaves communication characteristics exposed. Packet size, frequency, and session duration still provide valuable detection clues.

Processes performing actions without user interaction offer important context. Unexpected command execution or configuration changes often align with external control.

Individual indicators may appear harmless in isolation. Similar signals observed across multiple systems strengthen confidence in coordinated C2 activity.

Defense against C2 activity focuses on reducing attacker control rather than addressing only the initial compromise. Limiting communication, visibility, and persistence weakens the effectiveness of C2 servers.

Separating systems reduces how far C2-driven activity can extend. Compromised devices lose value if access to critical resources remains restricted.

Outbound communication should follow clearly defined rules. Limiting external connections reduces available paths for C2 channels.

Expected system behavior provides a baseline for comparison. Deviations in process activity or network usage often indicate hidden control.

Local activity reveals details that network data alone cannot capture. Monitoring processes and configuration changes helps surface C2-related actions.

External intelligence adds context to internal observations. Known indicators and behavioral patterns strengthen confidence in identifying C2 activity.

Priority shifts to limiting communication once control is suspected. Isolating affected systems prevents further instructions from reaching compromised hosts.

Reducing unnecessary services and permissions lowers the attack surface available for control mechanisms. Hardened systems offer fewer opportunities for persistent communication.

Defensive controls require regular reassessment as attacker techniques evolve. Ongoing evaluation helps close gaps before they are exploited.

Command & Control (C2) servers show how cyberattacks extend beyond the moment a system is compromised. Continued communication allows attackers to control malware, adjust activity, and retain access over time.

Focusing on C2 activity shifts attention toward communication and control rather than isolated incidents. Disrupting these channels reduces attacker influence and limits the duration and impact of intrusions.

Yes, in cybersecurity contexts, C2 servers refer to systems used to control malware or compromised devices. Legitimate remote management tools are not considered C2 servers because they operate with authorization.

No, a botnet is the group of compromised devices, while a C2 server is the system that controls them. The C2 server issues commands, and the botnet executes them.

Yes, encryption can hide the contents of C2 communication. It does not hide traffic patterns such as timing, frequency, or destination.

No, constant communication is not required for C2 control to function. Periodic or intermittent contact is enough to maintain control.

No, removing malware does not always immediately end C2 activity. Residual access, reinfection paths, or incomplete cleanup can allow control to persist.