🚀 CloudSEK becomes first Indian origin cybersecurity company to receive investment from US state fund

Read more

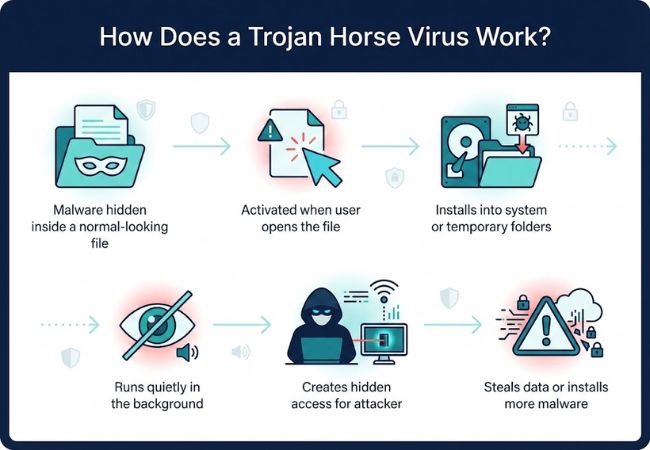

Trojan Horse attacks rarely begin with anything suspicious. Most start with a file that looks normal enough to open without a second thought.

That single action is usually all it takes for the malware to get inside a system and stay there quietly. No warnings appear, and nothing obvious breaks at first.

Over time, these infections lead to data loss, account compromise, or deeper system access that feels difficult to trace back. Knowing how Trojans work makes it easier to recognize risk before damage becomes visible.

A Trojan Horse virus is malware that hides inside something that looks harmless or useful, making it easy for users to trust and open it. Once launched, the malicious code inside begins operating quietly in the background.

Its name comes from an old story of soldiers concealed inside a wooden structure used to infiltrate a guarded city. In computing, attackers use a similar tactic by placing malicious code inside files that look completely ordinary.

Trojans do not spread automatically and rely on user interaction to begin their activity. This reliance on deception helps them blend into many environments and avoid early detection.

Early Trojan programs emerged during the first wave of personal computers, a time when many users had limited awareness of digital threats. Curiosity often led people to open unfamiliar files that carried destructive instructions.

Internet growth in the 1990s created new paths for distribution through email attachments and free software downloads. Trust in familiar senders made many individuals easy targets during that era.

By the 2000s, Trojan activity shifted toward financial theft, surveillance, and targeted attacks orchestrated by organized cybercrime groups. Gradual changes in technique allowed these threats to remain hidden for long periods in both home and business systems.

A Trojan starts its process by appearing safe, inviting users to interact with it without considering hidden risks. After that interaction, a chain of actions unfolds that quietly gives attackers access or control.

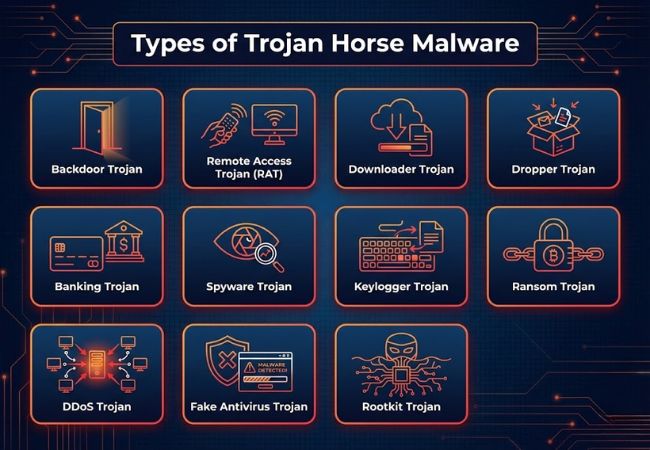

Trojan Horse malware appears in multiple forms because attackers adapt their methods based on goals such as access, control, data theft, or long-term concealment.

Backdoor Trojans became widespread once attackers realized a single successful infection could be reused for repeated access. Their main value is persistence, not immediate disruption.

A backdoor lets an attacker return later to manage files, change settings, or plant additional tools. Many long-term breaches still depend on this kind of quiet foothold.

RATs grew out of the same concepts used in legitimate remote administration software, but without consent or visibility. Full device control becomes possible even when the attacker is nowhere near the machine.

Files can be explored, commands can be executed, and user activity can be watched in real time. In many cases, the victim keeps using the device normally while monitoring continues.

Downloader Trojans became more common as security tools improved at catching “all-in-one” malware. Splitting access from payload delivery made infections easier to scale and harder to block early.

These Trojans connect out and pull in whatever comes next, based on attacker goals. Ransomware, spyware, and credential stealers often arrive through this second stage.

Droppers exist to hide what is truly being installed until the moment execution happens. This approach reduces the chance that scanners spot the real payload while the file is sitting on disk.

Execution releases hidden components into the system and installs them quickly. Detection often happens late, when secondary malware begins leaving visible traces.

Banking Trojans rose with the growth of online banking and digital payments, where credentials translate directly into money. Instead of breaking systems, these Trojans focus on quietly capturing sensitive access.

Victims can be tricked through fake login pages, altered browser sessions, or injected prompts during real transactions. Losses often show up first, and root cause becomes clear only later.

Spyware Trojans are built for ongoing collection rather than fast impact. Their strength comes from staying active long enough to gather valuable patterns and private content.

Messages, browsing activity, and stored documents can be copied without obvious disruption. Exposure grows over time, especially when captured data gets reused across accounts.

Keylogger Trojans focus on one job: recording what gets typed. Passwords, one-time codes, private messages, and search terms all become useful from that stream.

Even a short infection can leak access to email, banking, and work logins. Attackers often combine keylogging with spyware to capture context around stolen credentials.

Ransom Trojans existed before modern ransomware became mainstream, and early versions mainly restricted access rather than encrypting everything. Current campaigns often use a Trojan stage to prepare conditions for full ransomware deployment.

Systems get profiled, valuable files get identified, and defenses may be weakened quietly. Encryption or lockout happens later, which is why early signs can be easy to miss.

DDoS Trojans expanded as botnets became a reliable way to monetize compromised devices. Many infections focus less on harming the device owner and more on using that device as infrastructure.

Compromised systems generate traffic floods against targets, often on command. Owners frequently notice nothing besides occasional performance dips.

Fake antivirus Trojans grew popular when scare tactics proved profitable at scale. A clean interface and urgent warnings can pressure users into bad decisions quickly.

Victims may be pushed into paying for fake cleanup or installing even more malware. Fear drives the interaction, and the infection deepens with every click.

Rootkit Trojans exist for concealment, especially when attackers want long-term access without being hunted out. System-level hiding makes ordinary checks and many tools less effective.

Core components can be modified to mask malicious processes and files. Removal often requires deep cleanup steps, and sometimes a full reinstall becomes the safest option.

Trojan infections usually happen when users unknowingly interact with files, links, or software that attackers have designed to appear legitimate.

Phishing emails deliver Trojans through attachments or links disguised as invoices, alerts, or shared documents. Opening the file or clicking the link starts the infection without requiring any technical exploit.

Trojans are commonly bundled with free software, cracked programs, or fake tools downloaded from untrusted sources. Installation gives the malware the same permissions as the software it pretends to be.

Attackers often imitate system or application updates to spread Trojans. Users who trust these prompts install malware while believing they are improving security or performance.

Social engineering relies on urgency, fear, or curiosity to influence behavior. Messages that pressure users to act quickly reduce the chance of careful inspection.

USB drives and external storage devices can carry Trojan-infected files. Plugging them into a system may trigger execution through user interaction or autorun features.

Trojan Horse malware causes harm by giving attackers control, visibility, or leverage over systems rather than creating immediate, obvious disruption.

Sensitive information such as personal files, login credentials, and financial records can be copied without notice. Stolen data is often reused for fraud, identity theft, or resale.

Usernames, passwords, and authentication tokens are frequently captured during normal activity. Access to one account often leads to wider exposure across connected services.

Attackers may gain the ability to modify files, install programs, or change system settings. This control allows further abuse without repeated user interaction.

Banking Trojans and related payloads enable unauthorized transactions and account misuse. Losses may occur before any technical issue is detected.

Compromised devices can be used as entry points into larger networks. Internal systems become exposed once trust boundaries are crossed.

Some Trojans remain active for extended periods to monitor behavior and collect information. Ongoing access increases impact over time rather than all at once.

Trojan infections stay hard to spot because many variants are built for stealth and long-term access rather than instant disruption.

Unusual lag, frequent crashes, or overheating can indicate hidden background processes consuming CPU and memory. Suspicion increases when the system slows down during simple tasks like browsing or opening files.

Unknown processes, odd file names, or unsigned executables can show up in Task Manager or system activity monitors. Startup entries and scheduled tasks often reveal persistence mechanisms used by Trojans.

Command-and-control communication often appears as repeated outbound connections to unfamiliar domains or IP addresses. Network logs may show beaconing patterns, unusual ports, or encrypted traffic from apps that normally do not use it.

Endpoint Detection and Response tools often flag behaviors like suspicious process injection, credential dumping attempts, or abnormal script execution. Repeated detections tied to the same parent process usually signal an active infection chain.

Unauthorized logins, repeated failed sign-in attempts, or password reset emails can indicate credential theft linked to keyloggers or spyware Trojans. MFA prompts that you did not trigger are also a strong warning sign.

Disabled antivirus protection, modified firewall rules, or blocked security updates often point to defense evasion. Trojans commonly weaken protection first to reduce detection risk.

Preventing Trojan infections depends on limiting user exposure, reducing system trust by default, and detecting suspicious behavior before damage occurs.

Most Trojans enter through malicious attachments or links delivered by email. Strong filtering reduces exposure before users ever interact with harmful content.

Applications downloaded from unofficial sites frequently carry hidden malware. Restricting installs to trusted publishers lowers risk significantly.

Outdated operating systems and applications provide easy entry points for Trojan payloads. Regular updates close vulnerabilities that attackers rely on.

Modern antivirus and endpoint detection tools monitor behavior rather than relying only on known signatures. This approach helps identify Trojans that disguise themselves as legitimate software.

Running systems with limited user permissions reduces what a Trojan can change after execution. Administrative access should be granted only when necessary.

Outbound traffic analysis helps detect command-and-control communication early. Abnormal connection patterns often reveal infections that remain invisible on the system itself.

Trojan attacks succeed when trust replaces caution. Training users to question unexpected files, links, or prompts reduces successful infections.

Trojan Horse malware remains effective because it relies on trust rather than technical force. A single careless interaction can give attackers access that lasts far longer than expected.

Understanding how Trojans work, how they spread, and how damage unfolds makes early detection far more likely. Strong security controls combined with informed user behavior remain the most reliable defense against this type of threat.