🚀 CloudSEK becomes first Indian origin cybersecurity company to receive investment from US state fund

Read more

Key Takeaways:

Social engineering is a psychological manipulation method that influences people into giving away confidential information or performing risky actions. It relies on human emotion, trust, and instinct rather than technical vulnerabilities.

Attackers use persuasion techniques such as authority, urgency, or familiarity to make their requests appear legitimate. These tactics are designed to bypass logical thinking and trigger quick, unverified decisions.

The effectiveness of social engineering comes from its focus on human behavior, which is harder to secure than technology. As a result, it remains one of the most commonly used strategies in modern cyberattacks.

Social engineering takes several forms, each using different psychological triggers to manipulate victims.

Pretexting relies on fabricated scenarios or identities to convince victims to share information or take specific actions. Canada’s Maple Disruption 2025 update recorded 119 reports and 324 disruption actions linked to “bank investigator” pretexting patterns, showing how easily scripted narratives scale.

Baiting uses attractive offers or rewards to lure victims into unsafe behaviors such as downloading malicious files or entering sensitive data. INTERPOL’s Operation Red Card identified more than 5,000 victims tied to broad lure campaigns, demonstrating how baiting succeeds through volume.

Tailgating occurs when attackers gain physical access by following authorized users into restricted areas. A 2026 survey by ASIS International found that 61% of organizations cited tailgating (piggybacking) as the most common failure of physical access control systems.

Scareware pressures victims with alarming warnings to trigger fast, emotionally driven decisions. An FBI San Diego review reported a 2025 scheme targeting over 500 seniors with losses exceeding $40 million, illustrating how fear-based manipulation can cause significant harm.

Quid pro quo attacks promise help, rewards, or opportunities in exchange for information or access. Australia’s National Anti-Scam Centre reported actions including 836 crypto wallets blocked and nearly 29,000 fraudulent accounts removed, reflecting the scale of job-offer-style scams.

Impersonation uses false identities such as officials, coworkers, or service providers to gain trust quickly. Singapore Police Force data shows government-official impersonation affecting 12.7% of young senior victims, highlighting the ongoing effectiveness of authority-based deception.

Phishing is a form of deception where attackers send misleading emails, text messages, or voice calls to obtain sensitive information. These communications are crafted to look legitimate so the recipient feels confident responding.

The intent is to push people into actions like sharing login credentials or visiting unsafe links. Attackers use urgency, authority, or familiarity to make these requests feel routine.

Its reach across common communication channels makes phishing easy to distribute and hard to filter completely. This widespread accessibility is why it remains one of the most persistent cybersecurity threats today.

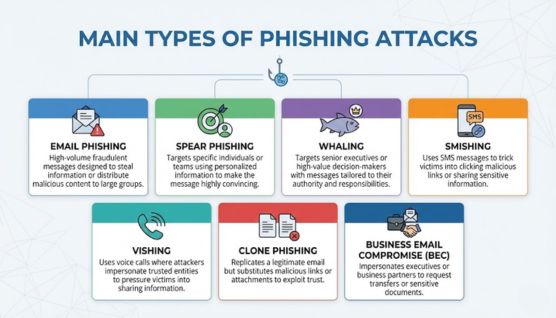

Phishing appears in multiple forms, each using different communication channels and levels of personalization.

Email phishing sends fraudulent messages to large groups in an attempt to steal information or distribute malicious content. The UK NCSC’s Annual Review 2025 reports 10.9 million email reports in the last year and over 45 million since 2020, showing how email remains the highest-volume phishing channel.

Spear phishing targets specific individuals or teams using personalized information to make the message highly convincing. Victoria OVIC’s Incident Insights recorded 561 notifications in early 2025 and highlighted email compromise as a major factor, reflecting how targeted email entry often precedes account breaches and data exposure.

Whaling targets senior executives or high-value decision-makers with messages tailored to their authority and responsibilities. Loss of concentration in high-impact unauthorized access and payment-redirection incidents aligns with well-documented whaling outcomes in real compromise patterns.

Smishing uses SMS messages to trick victims into clicking malicious links or sharing sensitive information. India’s Press Information Bureau reported the blocking of over 9.42 lakh SIM cards and 263,348 IMEIs tied to cyber fraud, highlighting how smishing operations rely heavily on disposable telecom infrastructure.

Vishing uses voice calls where attackers impersonate trusted entities to pressure victims into sharing information or authorizing transactions. According to Japan’s National Police Agency, 13,213 special fraud cases were recorded between January and June 2025, resulting in ¥59.7 billion in losses, including ¥38.9 billion from fake police scams.

Clone phishing replicates a legitimate email but substitutes malicious links or attachments to exploit the trust built by the original message. ENISA’s Threat Landscape 2025 notes phishing as ~60% of intrusion vectors and documents industrialized, AI-supported clones reaching 169 targets across 88 countries.

BEC impersonates executives or business partners to request transfers or sensitive documents. Australia’s ASD/ACSC Cyber Threat Report 2024–25 lists BEC as accounting for 15% of top self-reported business cybercrime losses, confirming it as a mainstream financially driven threat.

Phishing is indeed a form of social engineering because it relies on human manipulation through deceptive messages rather than technical exploits. It uses communication channels to influence behavior and extract information.

This categorization places phishing within the larger family of human-centered attack patterns, including pretexting, impersonation, and baiting. All of these methods depend on psychological triggers like trust, authority, and urgency to succeed.

Understanding phishing as one branch of social engineering helps organizations design security policies that address both message-based deception and broader behavioral risks. It also sets the stage for comparing how these two concepts differ in scope, technique, and operational intent.

Social engineering and phishing differ across scope, delivery methods, targeting, and operational intent.

Phishing prevention relies on combining technical safeguards with consistent user awareness.

Email filtering blocks suspicious or spoofed messages before they reach users. These systems evaluate sender identity, link behavior, and attachments to reduce exposure.

SPF, DKIM, and DMARC verify whether incoming emails are sent from authorized domains. Enforcing these controls reduces the risk of spoofed messages appearing legitimate.

Multi-factor authentication adds a verification layer that stops account access even if credentials are stolen. It significantly reduces successful phishing-driven compromises.

Link scanning tools Inspect URLs for malicious behavior before users open them. This prevents access to credential-harvesting pages or malware-hosting sites.

Attachment scanning detects harmful files embedded within phishing messages. Automated analysis reduces the chance of malware or payload execution.

Training programs teach users to identify suspicious messages, urgent requests, and unusual sender behavior. Awareness helps reduce mistaken clicks and impulsive responses.

Clear reporting processes allow employees to flag suspicious messages quickly. Fast escalation helps contain threats and improves incident response.

Effective protection requires evaluating tools and processes that address both human manipulation and message-based attacks.

High detection accuracy ensures the system can identify spoofed messages, impersonation attempts, and behavioral anomalies. Reliable detection reduces the number of high-risk threats reaching users.

Behavioral analysis monitors unusual activity patterns that may indicate manipulation or credential misuse. This adds depth to security by catching attacks that bypass message-based filters.

Email security tools validate senders, inspect message content, and enforce authentication protocols. These controls reduce exposure to phishing attempts delivered through email channels.

Training quality determines how well users recognize suspicious communication and manipulation cues. Consistent, scenario-based training strengthens human risk awareness.

A clear reporting workflow helps users escalate suspicious messages or interactions quickly. Fast reporting improves incident response and limits the spread of attacks.

Zero-trust alignment ensures every user, request, and device is continuously verified. This framework reduces the impact of successful phishing or social engineering attempts by limiting implicit trust.

Social engineering and phishing differ in scope, but both rely on manipulating human behavior rather than exploiting technical flaws. Recognizing this shared foundation helps organizations strengthen their overall human-risk defenses.

Phishing focuses specifically on deceptive communication channels, while social engineering encompasses a wider range of psychological tactics used both digitally and in person. Understanding this distinction makes it easier to design targeted training and security controls.

Effective protection comes from combining strong verification habits, consistent awareness programs, and layered technical safeguards. This integrated approach significantly reduces the likelihood of falling for either social engineering or phishing attacks.