🚀 أصبحت CloudSek أول شركة للأمن السيبراني من أصل هندي تتلقى استثمارات منها ولاية أمريكية صندوق

اقرأ المزيد

Cyber espionage has become a defining threat in modern cybersecurity because critical government and business intelligence now resides on connected systems. Instead of causing immediate disruption, attackers quietly access networks, monitor activity, and extract sensitive information over extended periods, often without alerting the victim.

According to Mandiant’s M-Trends 2023 Report, 63% of intrusions investigated were attributed to state-sponsored groups. Alarmingly, the median dwell time for these advanced persistent threats (APTs) was 16 days, but in many cases, intrusions went undetected for over 200 days, allowing continuous theft of diplomatic, military, research, and intellectual property data.

Understanding how cyber espionage works, who conducts it, the techniques involved, and the methods to detect and mitigate long-term intelligence theft can help organizations prevent significant damage.

Cyber espionage is the covert theft of sensitive digital information to gain a strategic intelligence advantage. The objective is sustained access to classified data, including government intelligence, military strategy, trade secrets, scientific research, or policy communications.

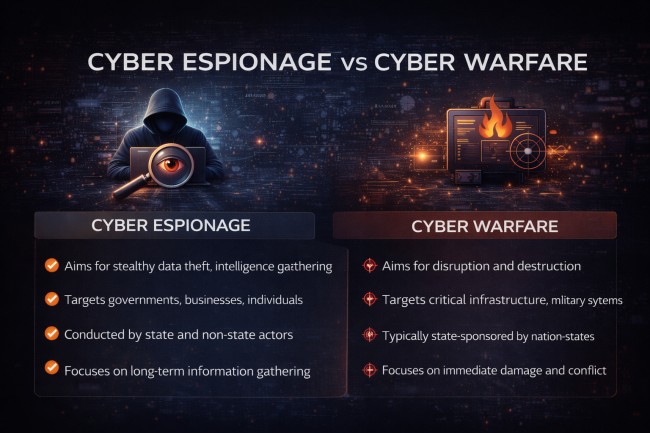

Unlike profit-driven cybercrime or disruption-focused cyber warfare, cyber espionage prioritizes stealth and long-term persistence. Threat actors infiltrate networks, maintain hidden access, and extract intelligence gradually over extended periods, reducing detection probability.

Cyber espionage targets high-value entities such as government agencies, critical infrastructure operators, research institutions, and intellectual property–driven enterprises. These operations are frequently attributed to nation-state or state-sponsored groups, defined primarily by their intelligence-collection intent rather than financial gain or immediate system damage.

Cyber espionage is driven by long-term strategic objectives, not short-term disruption or financial gain. Each goal reflects a specific advantage attackers seek to build and maintain over time.

Governments use cyber espionage to understand the plans, capabilities, and intentions of other nations. Access to diplomatic communications, internal government data, and intelligence assessments helps shape foreign policy and national security decisions.

Cyber espionage gathers information on military systems, defense technologies, troop movements, and strategic planning. This intelligence reduces uncertainty during conflict and strengthens long-term military readiness.

States target industries, corporations, and research organizations to obtain trade secrets, product designs, and proprietary technology. Stolen intelligence accelerates domestic development and lowers the cost of innovation.

Advanced research in areas such as aerospace, semiconductors, artificial intelligence, energy, and biotechnology is a frequent target. Access to scientific data shortens development cycles and supports strategic technological leadership.

Espionage campaigns collect information on political leaders, negotiations, and policy discussions. This insight enables influence over negotiations, anticipation of decisions, and leverage in international relations.

Some operations focus on maintaining continuous access rather than stealing specific data. Persistent visibility allows attackers to monitor changes, track decision-making, and respond quickly as new intelligence emerges.

Cyber espionage and cyber warfare are often confused, but they differ clearly in purpose, visibility, impact, and risk of escalation. Here are some points with key differences:

Cyber espionage is conducted by actors with state-level objectives and long-term intelligence goals, not by opportunistic criminals seeking quick profit. The groups below are most commonly responsible for espionage campaigns.

These are official government teams dedicated to foreign intelligence collection through digital means. They operate under national authority and focus on political, military, and strategic information.

These groups act on behalf of governments while maintaining operational separation. This structure provides deniability while allowing sustained intelligence collection against specific countries or sectors.

APT groups specialize in stealthy, long-term intrusions. They adapt to defenses, maintain persistence, and collect intelligence quietly over extended periods, often years.

Some espionage operations are carried out directly by military intelligence branches. Their focus includes defense capabilities, adversary readiness, and strategic planning information.

Governments sometimes rely on contractors or aligned groups to support cyber espionage efforts. These actors provide technical capability or infrastructure while remaining closely linked to state objectives.

Cyber espionage targets are selected based on the strategic value of the information they hold, not how easy they are to breach. Any organization that influences national security, economic strength, or long-term decision-making can become a target.

Government departments hold sensitive policy documents, diplomatic communications, and internal decision records. Access to this information reveals national priorities, negotiation positions, and future plans.

Military institutions store classified data related to weapons systems, operations, and strategic planning. Cyber espionage against these targets reduces uncertainty during conflict and strengthens adversary preparedness.

Organizations managing energy, transportation, telecommunications, and utilities are targeted to understand system design, dependencies, and resilience. The goal is intelligence gathering rather than immediate disruption.

Companies developing advanced technology, manufacturing processes, or proprietary software are frequent targets. Espionage focuses on stealing designs, source code, and research that support long-term technological advantage.

Academic organizations conduct valuable research in science, healthcare, engineering, and defense-related fields. Their open collaboration models and shared networks make them attractive intelligence sources.

These institutions influence government decisions through research and analysis. Access to their data provides insight into policy direction, strategic debates, and future regulatory approaches.

Large enterprises and smaller vendors are targeted because they support governments, defense programs, or critical industries. Espionage often uses supply-chain access to gather intelligence indirectly or reach higher-value targets.

These targets show that cyber espionage is intelligence-driven rather than attack-driven. Any organization holding information with strategic relevance can become part of an espionage campaign, regardless of size or visibility.

Cyber espionage relies on quiet, targeted, and persistent techniques that allow attackers to collect sensitive information without being noticed. These methods are chosen to minimize noise, avoid disruption, and maintain long-term access.

Attackers begin by studying the target in detail. They gather information about people, systems, technologies, and daily operations using public sources and internal observation. This preparation helps attackers select low-risk entry points and plan movement inside the environment.

Highly targeted emails or messages are sent to specific individuals within an organization. These messages are tailored to the recipient’s role or current activity and often appear legitimate. When victims interact with them, attackers gain initial access or steal credentials.

Usernames, passwords, or authentication tokens are stolen and reused to log in as legitimate users. This trusted access allows attackers to move laterally across systems and access sensitive resources without triggering obvious alerts.

Custom malware is deployed to maintain access and collect information over time. These tools are designed to blend into normal system activity, remain hidden, and survive security cleanup efforts.

Attackers abuse built-in system tools and administrative utilities instead of deploying obvious malware. This approach reduces forensic traces and helps malicious activity blend into normal operations.

Trusted vendors, service providers, or software updates are infiltrated to gain indirect access to high-value targets. By exploiting trust relationships, attackers avoid direct confrontation with hardened defenses.

Sensitive information is collected gradually and exfiltrated in small amounts. Data is often disguised as normal network traffic to avoid detection and preserve access.

These techniques are executed as part of coordinated, long-term campaigns. APT operations combine multiple methods, adapt to defensive measures, and prioritize persistence and intelligence value over speed or visibility.

Together, these techniques explain why cyber espionage is difficult to detect and disrupt. The deliberate use of low-noise methods and trusted access allows attackers to operate quietly while extracting intelligence over extended periods.

Cyber espionage follows a structured, long-term attack lifecycle focused on gaining access, staying hidden, and collecting intelligence over extended periods. Unlike disruptive attacks, every stage is designed to minimize detection and preserve ongoing visibility into the target environment.

The process begins with strategic reconnaissance, where attackers study public information, technologies, employees, partners, and exposed systems to understand how the organization operates and where valuable intelligence resides. Using this knowledge, they gain initial access through targeted methods such as spear phishing, stolen credentials, or trusted third parties, carefully avoiding security alerts.

Once inside, attackers establish persistence by deploying backdoors, abusing legitimate accounts, or creating hidden access paths that allow continued entry even if parts of the intrusion are discovered. Compromised systems then maintain covert command-and-control communication, enabling attackers to issue instructions, collect data, and adapt tactics while blending into normal network traffic.

With stable access in place, attackers perform lateral movement, quietly navigating systems using trusted credentials and built-in tools to reach high-value assets. They then conduct intelligence discovery and collection, selectively gathering sensitive emails, documents, research, and strategic data to avoid drawing attention.

Finally, collected intelligence is exfiltrated in small, controlled amounts, often hidden within legitimate traffic. Attackers reduce traces through anti-forensic actions such as log cleanup and infrastructure rotation, then continue monitoring and adapting over time to maintain access and intelligence flow.

These cases show a consistent pattern: state-backed attackers targeting high-value information through stealthy, long-term access. The timelines highlight how cyber espionage often remains undetected for months or years while intelligence is quietly extracted.

APT1 conducted long-running intrusions against dozens of U.S. organizations. The group stole proprietary designs, source code, and internal communications by maintaining persistent access for years, focusing on intellectual property and competitive intelligence.

APT28 compromised parliamentary systems through targeted phishing and malware. Attackers exfiltrated emails and internal documents, gaining insight into political decision-making and legislative activity.

During the SolarWinds supply chain compromise, APT29 infiltrated multiple U.S. agencies. The attackers used trusted software updates to gain access, then quietly collected emails and internal data for months before discovery.

APT10 targeted managed service providers to reach downstream clients. By exploiting trusted IT relationships, the group accessed corporate networks worldwide and stole sensitive business and technical information.

Lazarus conducted espionage campaigns against defense contractors using spear phishing and custom malware. The focus was on military technology, weapons research, and strategic defense data.

Cyber espionage is difficult to detect because it is designed to blend into normal activity and remain hidden for long periods. Detection depends on identifying subtle patterns, long dwell time, and correlated signals, rather than obvious attack alerts.

Stolen or abused credentials behave differently from real users over time. Logins at odd hours, access from unexpected locations, or repeated use of accounts outside normal roles can indicate espionage activity.

Espionage campaigns often maintain access for months or years. Systems that show recurring connections, persistent accounts, or access that survives remediation attempts may indicate ongoing intelligence collection.

Instead of large data transfers, attackers exfiltrate information in small amounts over extended periods. Consistent low-volume outbound traffic to unfamiliar or rarely used destinations is a common sign.

Attackers frequently rely on built-in system utilities and administrative tools. When trusted tools are used in unusual ways or outside standard workflows, they can indicate living-off-the-land activity.

Compromised systems may communicate regularly with external infrastructure while appearing benign. Repeated connections to newly registered, rarely visited, or geographically unusual domains can signal hidden control channels.

Detection often occurs when internal activity aligns with known espionage campaigns. Threat intelligence about domains, IPs, or techniques linked to nation-state groups provides critical context.

Individual signals may seem harmless in isolation. Correlating identity, network, endpoint, and external intelligence data over time reveals patterns that expose espionage operations.

Effective detection relies on correlation, context, and patience, not single alerts or isolated tools. Because cyber espionage unfolds slowly, sustained visibility across internal and external activity is essential to uncover it before long-term intelligence loss occurs.

Preventing cyber espionage requires reducing exposure, limiting trusted access, and maintaining continuous visibility across systems, identities, and data. Here are some tactics that help to prevent and mitigate cyber espionage:

Strong identity security limits the usefulness of stolen credentials. Enforcing multi-factor authentication, least-privilege access, and regular access reviews reduces the attacker’s ability to move quietly as a trusted user.

Public-facing assets often become entry points for espionage. Regularly identifying exposed systems, misconfigurations, and forgotten services helps eliminate access paths that attackers rely on during reconnaissance.

Espionage activity blends into normal operations. Monitoring for unusual login patterns, abnormal tool usage, and long-term access anomalies improves detection of low-noise intrusions.

Segmentation limits lateral movement after initial access. When sensitive systems are isolated, attackers struggle to reach high-value data even with valid credentials.

Administrative accounts are prime espionage targets. Limiting privileged access, monitoring administrative actions, and rotating credentials reduces the risk of silent compromise.

Vendors and service providers introduce indirect risk. Assessing third-party security, restricting vendor access, and monitoring trusted connections helps prevent supply chain–based espionage.

Internal signals become meaningful when combined with external intelligence. Tracking known attacker infrastructure, tactics, and campaigns improves early detection and response accuracy.

Espionage incidents rarely end quickly. Incident response plans must account for persistence, re-entry attempts, and extended investigation to fully remove attackers and validate cleanup.